Lesson Description

As sleek, shiny metal replaced wood in cars and airplanes, Art Deco’s stylized, geometric forms captured America’s craze for speed and design. In this lesson, students learn about 1920s and 1930s design and how architects and artists expressed the Machine Age ideals in their works. Students study William Van Alen’s Art Deco–style Chrysler Building and Minna Citron’s painting Staten Island Ferry. They compare the depiction of the Chrysler Building in each and its impact on those viewing Manhattan’s skyline at the time. Students will demonstrate their understanding by writing a narrative based on art.

Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will be able to:

- Describe American design in the 1920s and 1930s.

- Identify hallmarks of the Art Deco style in design.

- Write a narrative based on art.

- Explain how artists and architects included references to Machine Age mass production and America’s fascination with speed.

Learning Standards

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.2

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RI.8.7

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.8.2.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.SL.9-10.1

National standards for Visual Arts Education:

Grades 9–12 Content Standard 2

Using knowledge of structures and functions

Grades 9–12 Content Standard 3

Choosing and evaluating a range of subject matter, symbols, and ideas

Grades 9–12 Content Standard 4

Understanding the visual arts in relation to history and cultures

Grades 9–12 Content Standard 6

Making connections between visual arts and other disciplines

Lesson Activities

Activity: Look and Think

The Chrysler Building and Chrysler Autos

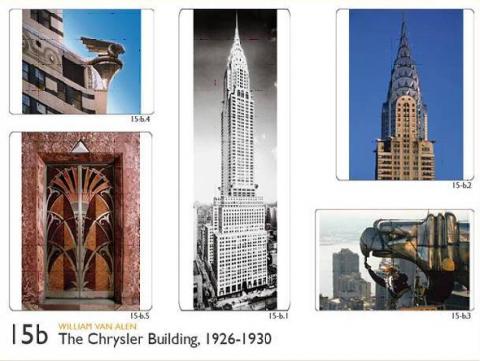

To conduct a more in-depth discussion of this building, each student should be able to see a large, clear image of the Chrysler Building and closeups of its ornamentation. Such an image may be downloaded from the Picturing America Educators Resources, Images for Classroom (Powerpoint), slide 15b.

After students have seen the video, ask:

+ What is surprising about this building?

+ How is it different from most office buildings?

+ How would you describe the overall shape of this building?

+ Notice how your eye is directed up the whole height of this building. How does the alignment of the windows contribute to this movement?

+ What else would you like to know about the Chrysler Building and its designer?

See information about the Chrysler Building on page 68 in the Picturing America Teachers Resource Book.

Point out that the top of the building is narrower than the lower stories. The building has a series of setbacks at the sixteenth, twenty-third, and thirtieth floors. New York City building regulations required that upper levels of tall buildings become narrower so that sunlight could reach the streets around these huge buildings. This one is seventy-seven floors and 1,046 feet high.

A stylized Egyptian papyrus plant decorates the elevator door. Howard Carter discovered King Tut’s tomb in 1922, and by 1926 New Yorkers were still interested in anything Egyptian.

Comparing Chrysler and Chrysler

Show students images of 1920s Chrysler automobiles, such as the ones found at:

Encourage students to find references to these cars on the Chrysler Building. About halfway up, giant winged radiator caps, similar to those on 1926 Chryslers, grace the building’s corners. Look for circular hubcaps behind these. The triangular windows in the crowning metal scallops suggest spoked wheels. Van Alen relates this fixed building to the shiny metal car.

Explain to students that the Chrysler Building is considered an excellent example of Art Deco design.

Activity:The Chrysler Building’s Impact on the New York City Skyline

Show students Minna Citron’s painting Staten Island Ferry.

Using a guided questioning approach, ask students:

+ What is happening in this artwork?

+ What do you see that makes you say that?

+ Where could this setting be? What makes you say that?

+ Who are these people, and what are they doing?

Have students identify buildings in the skyline that they recognize. Compare the image of the Chrysler Building in this artwork to the photographs they just observed.

Ask students what these people could have observed about the skyline. If they were traveling on this ferry into New York City, what would they be thinking?

Have students write a narrative letter describing their experience on the Staten Island Ferry, making sure they include the Chrysler Building in their experience.

Activity: Narrative Writing: My Trip on the Staten Island Ferry

Minna Citron depicts New York City in her painting Staten Island Ferry. The figures in the artwork are all shown actively engaged in the moment. If you were one of them, what would you be thinking, doing, and feeling?

Write a letter to someone from the perspective of one of the figures in the artwork. Be sure to include your impressions of the Chrysler Building and what it means to you at this moment.

Extending the Lesson

- Read The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925), to understand the role of cars and speed in the 1920s Jazz Age lifestyles of the rich.

- Construct a Machine Age sculpture from scrap-metal parts and hardware. Depending on the size of the recycled objects, join them together with wire, hot glue, or solder.

- Assign students to read “Can We Be Both Lighthearted and Serious? The Chrysler Building Shows How!,” an essay by Anthony C. Romeo, A.I.A., http://www.beautyofnyc.org/ChryslerBldg.pdf. Ask them to explain their answer to the title’s question.

Resources

Newark Museum Collection

Minna Citron

Born 1896, Newark, New Jersey

Died 1991, New York, New York

Staten Island Ferry, 1937

oil on Masonite

Purchase 1939 Felix Fuld Bequest Fund, 39.198

Minna Citron

Minna Citron was a member of the Fourteenth Street School, a group of Realist artists that included Kenneth Hayes Miller, Reginald Marsh, and Isabel Bishop. These artists worked in and around Fourteenth Street and Union Square, in New York City. Citron’s work demonstrates her lifelong interest in women’s independence. At the center of Staten Island Ferry stands a woman wearing a belted, bright blue dress, a style commonly worn by female office workers at the time. She directs the attention of her younger companion to the soaring skyline of New York, which can be seen as a symbol of opportunity. Citron draws the viewer’s attention to the woman’s red bag; the bag may suggest her self-sufficiency and control over her own financial resources.

National Endowment for the Humanities, Picturing America Collection

William Van Alen (1883–1954

The Chrysler Building

Manhattan, 1930

Photographic print

Library of Congress

Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, D.C.

William Van Alen (1883–1954) and the Chrysler Building

As America’s economy flourished during the roaring 1920s, wealthy businessmen raced to build ever taller skyscrapers. Walter P. Chrysler, head of the company manufacturing Chrysler automobiles, challenged architect William Van Alen to build him the tallest building in New York. Brooklyn-born Van Alen studied at Pratt Institute, in New York, won a scholarship to study in Paris, and was known for his flamboyant modern designs.

Like many modern European and American architects and designers, Van Alen embraced the Art Deco style. With its stylized, abstracted, natural forms and repeated geometric shapes, it lent itself to mass production and architecture. Art Deco designs were often metal, plastic, or glass, with bright colors. This decorative design style was influenced by Cubism’s simplification of forms, Futurism’s movement, and Constructionism’s architectural feel.

Walter Chrysler asked for “a bold structure, declaring the glories of the modern age.” The metal-topped Art Deco–style Chrysler Building features Chrysler automobile hood ornaments, hubcaps, and stylized eagle gargoyles reminiscent of Gothic drainspouts. When the Chrysler Building was completed, in 1930, it was the tallest skyscraper in Manhattan, but the Empire State Building topped it in 1931. Unfortunately, as the Great Depression took hold and Chrysler balked at paying Van Alen, this was the architect’s last major construction.

Learn more about William Van Alen and how he secretly assembled and installed the crowning steel tip to ensure that his seventy-seven-story building was Manhattan’s tallest skyscraper in Picturing America Teachers Resource Book, 15b, The Chrysler Building

Automobiles

At the beginning of the twentieth century, cars were fragile, expensive toys for the wealthy. But when Henry Ford began mass-producing Model Ts on his conveyor-belt assembly line in 1913, they became affordable to the middle class. Fifteen million Model Ts had been produced by 1927. Except in cities, roads were in such poor condition and drivers were so bad that travel was still slow and dangerous. Gradually, state legislatures passed laws to fund road construction, enforce traffic rules, and license cars and drivers. Only one-sixth of rural roads were paved in 1904, but by 1935 more than twice that had some surfacing. During the 1930s, America’s first transcontinental highway, the Lincoln Highway, between New York and California, was completely paved. By 1930, more than half of American families owned a car.

For more information, videos, and learning resources, visit the National Museum of American History’s website, America on the Move

Additional Resources

Selected NEH EDSITEment Websites

William Van Alen, The Chrysler Building, 15b

Picturing America Teachers Resource Book

The Chrysler Building

Picturing America on Screen

America on the Move

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

PBS Series

Chasing the Sun

Aviation history seen through the eyes of its innovators

Wonders of the World databank—Skyscraper, Chrysler Building

Library of Congress

Teacher's Guide: The Industrial Revolution

Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum

Airmail to Airlines—Teacher Guide

Selected EDSITEment Lesson Plans

Carl Sandburg's "Chicago": Bringing a Great City Alive

Egyptian Symbols and Figures: Scroll Paintings

Thomas Edison's Inventions in the 1900s and Today: From "New" to You!

Edith Wharton: War Correspondent

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication does not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Arts.