Lesson Description

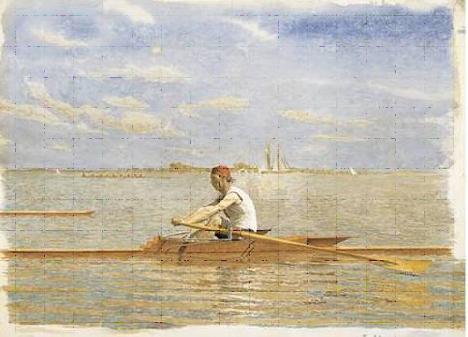

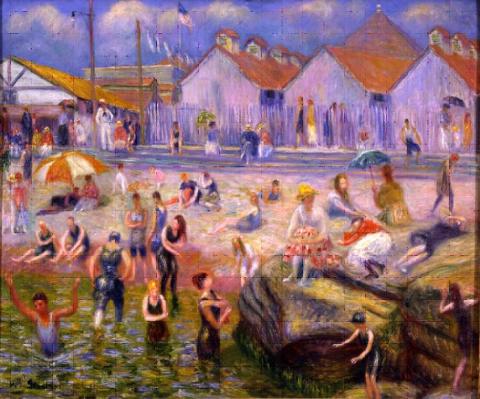

In 1918, William Glackens painted a crowded beach scene. How did all those Americans find time to play at the beach? Or watch boat races like those that Thomas Eakins painted in 1873? In 1870, most Americans worked more than sixty hours a week, but by 1919 the workweek had shrunk to about fifty hours. This shorter workweek had not come easily. During the last decades of the nineteenth century, reformers urged employers to improve working conditions. Strikes and labor rallies, like the 1886 Chicago Haymarket Square Riot, sometimes turned violent as workers demanded an eight-hour workday. By 1918, workers had gained an extra day of leisure to enjoy the beach or boat races or some other new pastime.

In this lesson, students view Thomas Eakins’s 1873 painting of John Biglin in a Single Scull and William Glackens’s 1918 At the Beach. Students read and write about the PBS Livelyhood article “How The Weekend Was Won.” After researching the Haymarket Square Riot, they write and illustrate an imagined diary entry by a worker who was present at the 1886 riot. Worksheets are included to help students analyze the art, understand the article about the history of the eight-hour workday, and research and write about the Haymarket Riot.

Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will be able to:

- Analyze, describe, and compare William Glackens’s oil painting At the Beach and Thomas Eakins’s watercolor painting John Biglin in a Single Scull.

- Describe several leisure activities of middle-class Americans in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

- Explain how and why the number of hours American employees worked per week declined during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

- Describe the 1886 Haymarket Square Rally and Riot.

Learning Standards

NAES–VisArts–5–8, 4

NAES–VisArts–5–8, 6

Common Core ELA Standards

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.7 Integrate and evaluate multiple sources of information presented in diverse formats and media (e.g., visually, quantitatively, as well as in words) in order to address a question or solve a problem.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.2 Write informative/explanatory texts, including the narration of historical events, scientific procedures/experiments, or technical processes.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.W.9-10.3 Write narratives to develop real or imagined experiences or events using effective technique, well-chosen details, and well-structured event sequences.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.9-10.2 Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source; provide an accurate summary of how key events or ideas develop over the course of the text.

Visual Arts Standards

Grades 9–12 Content Standard 4 Understanding the visual arts in relation to history and cultures

Lesson Activies

Activity: Look and Think Compare Two Artworks

Each student should have a good view of Glackens’s At the Beach and Eakins’s John Biglin in a Single Scull, either on a computer, a projection, or as printed color copies. Before discussing these paintings, have students study them silently and write their answers on Worksheet 1 Look and Think. Use the worksheet questions and students’ answers as a framework for class discussion about the artworks.

Download full PDF lesson above to access Activity Worksheets

Activity : How the Weekend was Won

Have students read the document included below about the labor reform movements and the Haymarket Riots.

Questions to Pose to the Class After Reading:

- If we assume that, traditionally, American Sundays were reserved for worship, and if an 1890s worker worked six days a week, how many hours did the person work each day?

- If he usually worked during daylight hours, when did he begin work each day and when did he go home?

- How many hours did he have for sleeping?

- When did he have enough time to go to the beach?

Download full PDF lesson above to access Activity Worksheets

Activity: Creating a Narrative

After reading about the Haymarket Square Rally of May 4 1886, and completing independent research on the event, students will create a diary entry and illustration from the perspective of an attendee of the rally.

They will create a diary that includes the following:

1. Who will you be, a man or a woman? How old are you?

2. What kind of work do you do? Is your work dangerous?

3. How many hours a week do you work? How many hours do you wish

you worked?

4. How much do you sleep? Are you tired or hungry?

5. What did you do on your day off? When was that?

6. Why did you go to the rally?

7. Who went with you to the rally?

8. What did you hope would happen at the rally?

9. What happened at the rally? What did you hear, smell, see, and feel?

10. How close were you to the speakers? The policemen? The bomb?

11. Do you know anyone who got hurt or killed?

12. Why do you think the riot broke out?

13. What did you do after the rally? Where did you go?

14. What do you think will happen after this? Do you think anything will

change?

Download full PDF lesson above to access Activity Worksheets

Activity:Three Dimensional Newark Museum Image

Show students a three-dimensional image from the Newark Museum teaching collection. These objects contributed to the idea of leisure time, however were made my someone working overtime.

Newark Museum Three-Dimensional Teaching Objects:

Women’s Hat

Women’s Shoes

Candle Mold

Ask students:

- What is this object

- Who would have used it?

- How would it be used?

- How was it made, and by whom?

- How would this profession be altered by imposing an eight-hour workday?

- How would lesiure time be altered if this object was not made?

Extending the Lesson

- Students may research a favorite American leisure activity from the end of the nineteenth to the beginning of the twentieth century. This could be a sport like bicycle riding, swimming, skating, baseball, basketball, or football. They may draw, paint, or make a collage about this activity. Printouts from newspaper illustrations found in Chronicling America can be included in their artwork. Students should write a description of their completed artwork, including the name of the activity depicted and a description of the clothing or equipment used in this activity. How is this activity different today? Tell them to explain why middle-class Americans at this time in history had the time and money to participate in this activity.

- Have students look at the Newark Museum’s three-dimesional image of a women’s hat from 1920. Have students describe the typical day for the woman who wore this hat. What did she do during her free time? What she a factory worker or did she stay at home? What did she do in her leisure time?

Resources

More Leisure Time

As the nineteenth century ended and the twentieth began, United States workers had more leisure time than in previous decades. Industrial employers began reducing the number of hours employees worked per day and giving employees a half-day off on Saturdays. In 1850, manufacturing employees worked more than sixty hours a week. By the 1920s, that amount had dropped to forty-eight, and dropped further to about forty hours per week in 1950. (Sources vary on these statistics.) Gradually, large numbers of workers gained more time for leisure activities. At the turn of the nineteenth century, employers began offering workers vacation time, but usually without pay. As cities became more crowded, however, and manufacturing jobs more monotonous, workers wanted time away from the city and their jobs. Progressive activists considered leisure time to be beneficial to workers’ health.

Learn more at:

How the Weekend Was Won, History Lesson, Livelyhood, PBS

and

Hours of Work in U.S. History, Economic History Association

Labor

America’s Gilded Age and Progressive Era were times of economic uncertainty for workers. Industries grew rapidly, and new workers from Europe crowded into the United States looking for jobs. As a result of the 1893 depression, plants closed, and labor disputes flared as workers sought safer working conditions and more reasonable working hours. Workers formed labor unions like the American Federation of Labor. These groups organized strikes and rallies to force managers to accept their demands. Sometimes, these strikes and rallies became violent, as police and strikebreakers were called in to end them. Chicago’s 1886 Haymarket Square Rally turned into a riot. President Theodore Roosevelt introduced reforms to major industries and supported workers’ rights. When Woodrow Wilson was president, laws were passed creating eight-hour workdays for railroad workers and curtailing child labor.

Learn more at:

America at Work, 1894–1915

The Artists

Although Thomas Eakins was twenty-six years older than William Glackens, they shared similar backgrounds. Both were born and raised in Philadelphia, attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and studied art in Paris. After Eakins returned to the United States he never traveled to Europe again, but Glackens continued to take frequent trips to Europe. Both artists went against the prevailing art styles of their day by painting scenes from everyday life.

Thomas Eakins (1844–1916)

John Biglin in a Single Scull, ca. 1873

watercolor on off-white wove paper,

19 5⁄16 x 24 7⁄8 {case fractions} in. (49.2 x 63.2 cm.)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Eakins was intent on painting realism with exacting, scientific studies of both perspectives and anatomy. As both an enthusiastic rower and a spectator of rowing competitions, he created nearly thirty pictures of rowers. In addition to studying art at the Pennsylvania Academy, Eakins studied anatomy at Jefferson Medical College to help him draw anatomically correct figures. Throughout his life, he painted his subjects as they actually appeared, rather than how they would like to be seen.

William Glackens (1870–1938)

At the Beach, ca. 1918

oil on canvas 25 1/4{case fraction} x 30 in.

After studying at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Glackens traveled to Paris and the Netherlands. On his return to the United States, he worked as a magazine illustrator in New York. In this capacity, he sailed to Cuba with the U.S. Army in 1898. By 1904, he was devoting himself to his painting. He was part of the Ashcan School and of a group of realist artists known as The Eight, who drew their subject matter from urban life. Initially, he painted his urban realism in muted tones similar to those of Robert Henri, his friend and teacher. In 1908, following another European trip, Glackens’s paintings of everyday life became more like the French Impressionists, with brighter colors and quick brushstrokes that resembled Renoir’s.

Glackens attended high school with art collector Albert C. Barnes. In 1912, Barnes sent Glackens to France to purchase works by such artists as Renoir, Matisse, and Cézanne for his collection. The following year, Glackens became chairman of the committee to select American art for the important Armory Show, which played a pivotal role in introducing contemporary European art to Americans.

Additional Resources

Selected EDSITEment Lesson Plans

Everything in its right place: An Introduction to Composition in Painting

Lesson 1: Shaping the View: Composition Basics

Lesson 2: Shaping the View: Symmetry and Balance

Lesson 3: Repeat After Me: Repetition in the Visual Arts

Lesson 4: Follow the Leader: Line in the Visual Arts

EDSITEment Page

Eakins's Vision of American Recreation—"In the Good Old Summer Time"

EDSITEment’s John Biglin and the Single Scull interactive

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication does not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Arts.