Lesson Description

During the Gilded Age, near the end of the nineteenth century, industrial and financial entrepreneurs amassed vast fortunes. These newly rich built huge mansions decorated with antiques and art to suggest their family’s ancient democratic heritage. Homes from this era often included stained-glass windows.

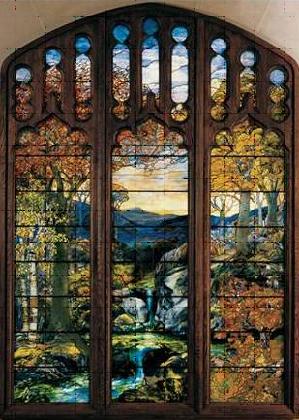

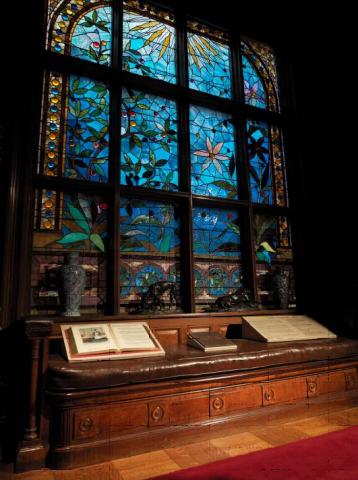

In this lesson, students compare and contrast Tiffany Studios’ Autumn Landscape—The River of Life window with an Art Nouveau and an Aesthetic movement window from the Ballantine House, in Newark. After researching a Gilded Age industrial or financial leader, students draw a design that represents him. They write an essay explaining how this leader’s work and wealth have influenced modern America.

Objectives

At the end of this lesson, students will be able to:

- Analyze the design in Tiffany Studios’ Autumn Landscape stained-glass window.

- Compare and contrast three stained-glass windows.

- Identify an Art Nouveau and Aesthetic movement window design.

- Write information about the life and philanthropies of a Gilded Age industrial or financial leader.

- Draw a design representing that leader.

- Write an essay explaining how that leader’s work still influences modern life.

Learning Standards

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.7.

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.WHST.11-12.1

CCSS.ELA-Literacy.RH.11-12.1

National Standards for Visual Arts Education

Grades 9–12 Content Standard 1

Understanding and applying media, techniques, and processes

Grades 9–12 Content Standard 4

Understanding the visual arts in relation to history and cultures

Grades 9–12 Content Standard 6

Making connections between visual arts and other disciplines

Lesson Activies

Activity: Look and Think Worksheet

Show students Tiffany’s Autumn Landscape—The River of Life stained-glass window. Use the Teaching Activities in the Picturing America Teachers Resource Book, 13b, to guide a careful discussion of the window. Have students watch the first half of Tiffany/Whistler, Picturing America on Screen

Next, show students the much smaller Fire Worshipper window from the Ballantine House, in Newark, New Jersey. Tell them that the homeowner wished this design to suggest his family’s roots in ancient Scotland. Have students write their observations about this window. Discuss their answers. Teach them that this is an example of Art Nouveau, with its serpentine curves and suggestion of wild nature.

Show students the huge, blue staircase window from the Ballantine House. Compare its flat background to the great distances seen in the Tiffany landscape. It is almost like a decorative wallpaper pattern; with its dark lines and stylized flowers, however, it suggests Japanese art. This window and Autumn Landscape were both designed to be decorative. These Aesthetic movement windows would bring beauty into everyday home life.

Have students compare and contrast the three stained-glass windows. They should all be able to see good-quality color reproductions of these windows as they write their comparisons. Discuss their answers.

Download full PDF lesson above access Activity Worksheets

Activity : Research a Gilded Age Industrialist

Have students research a Gilded Age industrial leader. Students should write information that they learn from their reading on the worksheet below about a Gilded Age industrial leader. They may read an online biography from one of the following websites:

- Andrew Carnegie biography, American Experience

- The Life of Henry Ford, Henry Ford Museum

- Henry Clay Frick,The Frick, Pittsburgh

- J. Pierpont Morgan, American Experience

- John D. Rockefeller, Senior, American Experience

Download full PDF lesson above access Activity Worksheets

Activity: Creating a Stained Glass Window

Students will create a stained-glass window for their researched industrialist.Show students Bob Vila TV shows Making Stained-Glass Windows. This video demonstrates how craftsmen use drawings to create stained-glass windows.

Have students draw a stained-glass design for the Gilded Age industrial leader they researched. They should include images of the words or phrases that they associate with this person.

Have students draw their design lightly in pencil on paper. They may choose to include a border in their design. Make the images large. Trace over the pencil lines with wide black marker lines. Cut out the area that will be “stained glass,” leaving the border outline intact. Place the border over tissue paper or clear colored plastic. This will produce the effect of a stained-glass window.

Extending the Lesson

Stage a roundtable discussion of Gilded Age industry leaders. Have students impersonate the leader whom they researched. What would these men say about today’s economy? Environment? Transportation? Taxes?

- Video about Gilded Age parallels to our age

Show students “Steve Fraser on the Gilded Ages,”

a Bill Moyers video interview with historian and author Steve Fraser, who discusses parallels and differences between the first Gilded Age and today's Gilded Age.

- Japanese influence in the Aesthetic movement

To gain a better understanding of Japanese art influences on the Aesthetic movement, students may examine Japanese prints. They should notice the dark lines surrounding flat areas of color and the stylized nature patterns in the kimonos. Compare these lines and patterns to those of the large stained-glass window on the staircase landing of the Ballantine House, in Newark, New Jersey.

Resources

Industry Leaders of the Gilded Age

Mark Twain called the late nineteenth century the “Gilded Age” because it glittered on the surface but was corrupt underneath. This was an era of rapid technological growth. Inventions proliferated—electricity, telephones, automobiles, airplanes, and much more changed American life. As the United States evolved into our modern era, the men who owned and controlled industry and commerce amassed huge fortunes.

Because their immense wealth was so much greater than the minimum wages and working conditions of their employees, these captains of industry have been called “robber barons.” This group of wealthy entrepreneurs included John D. Rockefeller, Cornelius Vanderbilt, Henry Clay Frick, Andrew Carnegie, and J. Pierpont Morgan. The unfettered capitalism of this era resulted in social conflicts and, eventually, the Progressive movements and reforms of the early twentieth century. Of course, the men saw themselves as merely exploiting and developing opportunities. Many of them and their families became philanthropists, contributing vast amounts of money to schools, libraries, museums, hospitals, and other public institutions.

As the new rich in a young nation, these families adopted European ideals of aristocracy. They considered themselves the heirs of the great Western tradition, extending from the Greeks to the Romans and the European Renaissance. They furnished their mansions with European antiques and art to suggest ancient family heritages and cultural roots.

Ballantine Ale

Peter Ballantine immigrated to the United States from Scotland in 1820. First, he worked in a Connecticut tavern and then in a brewery in Troy, New York, where he learned to brew beer. He finally saved enough money to start his own brewery. In 1840, he relocated to Newark, New Jersey, then known for its abundant supply of fresh water and proximity to New York City’s growing population. Over time, Peter Ballantine and his three sons expanded their plant, transporting beer throughout the New York area and the rest of the country.

Ballantine House

In 1883, one of Peter Ballantine’s sons, John H. Ballantine, became president of what was one of the largest breweries in the world. Immediately, he began planning a townhouse suitable to his position. He hired architect George Edward Harney to build a home for his family on Washington Park, in Newark. A New York City interior decorating firm, D. S. Hess, professionally decorated this three-story, twenty-seven-room Victorian home.

John Ballantine took a personal interest in the design of his family’s new home. He suggested the subject of the stained-glass window in the library be based on the family name. Ballantine is derived from the Scottish Gaelic words bael, which means fire, and antin, a worshipper. The window is attributed to Tiffany Studios and is probably the design of the painter Elihu Vedder. The window features a Celtic maiden extending her arms toward the sun and an incense burner wafting smoke into the sky. Family tradition suggests that John Ballantine was disappointed with the window: He had wished for brighter colors. Although the colors in this window are not as intense as other windows in the house, art critics consider it to be artistically more sophisticated.

Art Nouveau

The Fire Worshipper window’s Art Nouveau design is strikingly modern for 1885. Art Nouveau was popular in applied arts from the 1880s until World War I in the United States and Western Europe. The twisting lines and undulating curves inspired by nature are typical of Art Nouveau designs.

Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933)

Autumn Landscape—The River of Life, 1923–24

leaded Favrile-glass window, 11 ft. x 8 ft. 6 in., Tiffany Studios

Louis Comfort Tiffany’s studios created leaded-glass windows as well as blown glass, lights, pottery, jewelry, mosaics, and metal works. Tiffany trained as a painter with George Inness (1825–94) and Samuel Colman (1832–1920), but he was most interested in decorative arts and interiors.

Tiffany expanded the possibilities of glass design. In the early 1890s, he and Arthur Nash, a skilled English glassworker, developed a method of blending various colors of molten glass. With this Favrile, or hand-wrought, method they could create subtle shading and textural effects. Tiffany and his competitor John La Farge revolutionized the look of stained glass. Both Tiffany and La Farge experimented with glass to create a greater variety of colors in richer hues. They each developed opalescent glass that was opaque and milky and even rainbow-hued, depending on the light.

Learn more about Tiffany at Educators Resource Book, 13b

and

Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933), Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

Ballantine House staircase landing window

In the Ballantine House, the focal point of the staircase landing is a great, blue turquoise stained-glass window. The design of this twelve-panel window, with its stylized flowers and dark lines surrounding areas of flat intense color, shows the influence of Japanese art. This window faces west, so that the sun at the top seems to be setting over a garden of exotic, jeweled flowers. The background glass has a crackle pattern that changes to lavender in strong sunlight.

During the 1880s, large stained-glass windows like this were often placed in the landings of city houses. They allowed natural light into the home while obscuring the urban surroundings.

Aesthetic movement

In architecture and the decorative arts, the Aesthetic movement was a transitional style between late Victorian revivalism and the Arts and Crafts movement. Artists, designers, and decorators created beautiful objects and environments. They wanted homes of the middle class, as well as those of the very wealthy, to be visually beautiful and pleasurable to inhabit. Aesthetic designers often utilized strong colors such as bright blues, greens, and yellows. The sunflower was popular in this style because of its simple shape and bold color. It could symbolize warmth, sun, and fire. Japanese design was an important influence to this style.

Both of the huge decorative landing windows featured in this lesson fulfill the Aesthetic movement’s goal of bringing art into daily life.

Learn more about the Aesthetic movement at:

Aesthetic movement: Design Reform, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Elihu Vedder (1836–1923)

(1836–1923 and Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848–1933) studios attributed

Fire Worshipper, 1885,

leaded-glass window, approx. 3 x 5 ft., Ballantine House, Newark, N.J.

Elihu Vedder was born in New York but grew up in Cuba and on his grandfather’s Brooklyn farm. As a young man, he studied painting with François Édouard Picot, in France. When Vedder returned to the United States, just before the Civil War, he became a magazine illustrator but soon decided he did not enjoy the fast pace of this art profession. In 1865, he became a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. He continued to paint and live abroad, eventually settling in Italy. One of his most acclaimed works is his set of illustrations for Edward Fitzgerald’s translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. He also created murals for the walls of the Library of Congress.

Learn more about Elihu Vedder at

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and Elihu Vedder

and

Vedder, Elihu (1836–1923), The Vault at Pfaff’s, an archive of art and literature by New York City’s bohemians

Additional Resources

Selected EDSITEment Websites

Picturing America

Tiffany/Whistler

Picturing America on Screen

Newark Museum

American Experience

The Life of Henry Ford, Henry Ford Museum

Henry Clay Frick

The Frick, Pittsburgh

Cornelius Vanderbilt biography

Digital History

Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam and Elihu Vedder

Smithsonian Museum of American Art Exhibition

Vedder, Elihu, The Vault at Pfaff’s, an archive of art and literature by New York City’s bohemians

Any views, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication does not necessarily reflect those of the National Endowment for the Arts.